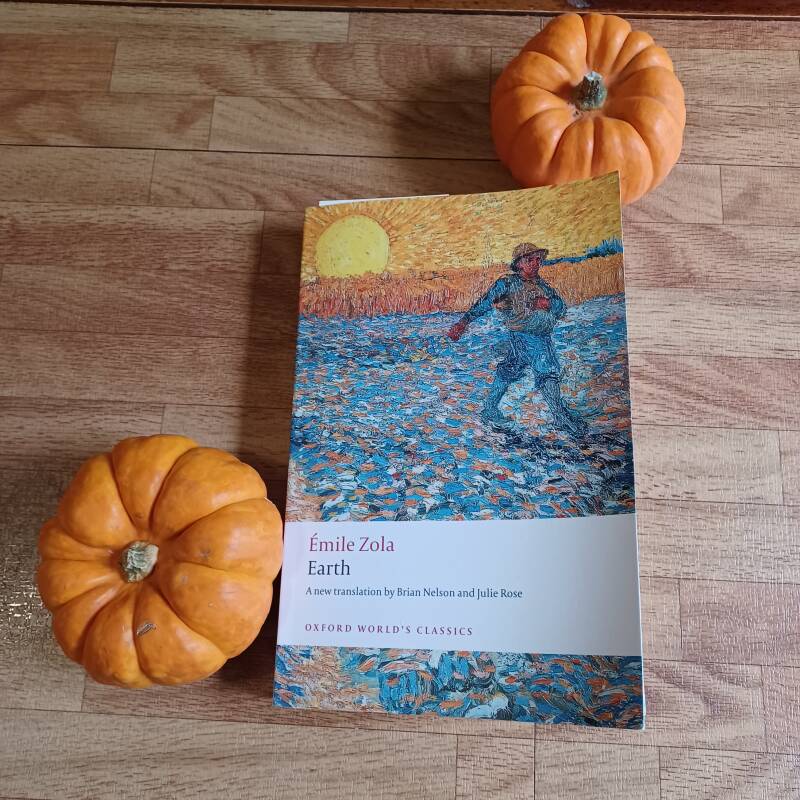

Uh-Oh, Zola again...

Surprise, Surprise she’s reading Zola again! And yes this is part of the Rougon-Macquart series of books and is actually the 15th novel. I was really excited about this one, as from the blurb it sounded like my kind of book. In my literary studies, I have enjoyed focusing on eco-criticism which is basically the portrayal of the environment and nature in literature. My friend knew I liked Zola and specially picked this one for me!

I was expecting long beautiful imagery of the French countryside, but Zola gave me the brutal, harsh reality of C19th century French peasant life. This novel was brutal, and often, even by today’s standards a very uncomfortable read.

Nothing can come of Nothing….

Although the plot deviates a lot, there is a central event at the beginning of the novel that precipitates the majority of the conflict in the novel. Set in Northern France in the C19th, it is set in the fictional village of Beauce, where the peasants till the soil, not for profit, for sheer survival; knowing eventually that it is the very soil they will return too (or be buried in).

The story is focused on the Fouan family. Farmer Fouan is getting old, and decides to divide all his land amongst 3 of his 4 children (the fourth gets her share in money instead).

As family relationships fray, his 3 children contribute less and less to his and his wife’s upkeep as he had made them promise, and he ends up regretful, bitter and homeless.

The most obvious example of this plot is of course, Shakespeare’s, King Lear. Where Lear gives away his Kingdom, but still expects the authority he yielded as King. Similarly, Fouan expects the respect from his children to sustain his ‘retirement’ (quotation marks because there was no such thing for this class of people then).

Fouan gives aways the very thing that sustains him and all of this society, the land.

Soil, Dirt, returning

AS the title implies, land and the soil is the life force of the society in this novel. It sustains and maintains life, but also depletes it as it requires constant labour upon it. It reduces each individual’s quality of life, as they work on it, lose it, bet on it, mortgage it and kill for it.

Depraved

The brutality of the novel comes of course from the constant agricultural labour in the novel, but Zola extends it to the morality of the people in this society too.

Firstly, there is a continued side plot of the local priest refusing to journey to the town to conduct mass. As a result of this, much to the surprise of the time, the people in this town are devoid of religious authority or basic Christianity.

Zola portrays the result of a society without such a moral basis. There is no expectation of behaviour or respect for one another. All the actions in the novel all lack moral sense, and are rather done out of pure greed or hatred for the person they are inflicting it on.

Nobody comes clean. Zola portrays all the indivudal’s as nothing above ‘savages’, where sisters fight sisters, and brother’s attack brothers and vice versa.

Ew, men

Whilst there are some land owning women in this novel, everything is decreed by male landowners. As the men are too the land, they are predatory towards women in the novel.

the sexual violence is prolific. Often very difficult to read, it is again portrayed as nothing more animalistic decisions and behaviours lacking any moral impulse to conduct oneself otherwise.

Farts

As a more funny example of the depraved portrayal of the characters in this novel, there is a guy that just farts his way through the book. Fouan’s peasant son, nicknamed ‘Jesus Christ’ because of his outrageous behaviour, responds to authority and responsibility, by farting.

He farts at debt collectors (literally the debt collector runs away as Jesus Christ farts), priests and anyone he can make laugh. Again, it is there to debase the character of these people.

The Body

Whether it is the physical agricultural labour, the sex or the farting everyone in this novel immorally indulges in the pleasure and pains of the body. There is the constant return to the impact of the environment on the body, being more destructive than anything humanity an inflict on the land, which is eternal.

Eternal renewal

The connection the Rougon Macquart series of books is Jean, who marries one of Fouan’s nieces. He begins as a stranger to the town and quickly gets wrapped up in the depraved drama of it all. He has also come from fighting in a war, which is another connection to land, from fighting for it, to working on it.

The novel comes full circle with the image of the renewed soil, with the book, opening and closing with the sowing of new seeds on the land.

Look after the Earth...

Whilst this book wasn’t the pretty little flowery book I was expecting, I nonetheless enjoyed it. It reaffirms, no matter what time period, humanities dependency on the land, and perhaps why we shouldn’t be destroying it as we currently are, as it is the very thing sustaining us.

Add comment

Comments